Damon Runyon News

View New Articles By

View New Articles By

Adoptive T cell therapies, in which a patient’s own immune cells are genetically engineered to target their cancer cells, have been remarkably effective in treating certain blood cancers. Unfortunately, this success has not translated to solid tumors, where T cells face unique challenges in the tumor environment that limit their persistence and function.

Few scientific studies meet with more controversy than those that suggest a substance may cause or prevent cancer. As a leading epidemiologist of colorectal cancer, former Damon Runyon Clinical Investigator Andrew T. Chan, MD, MPH, is no stranger to this rollercoaster.

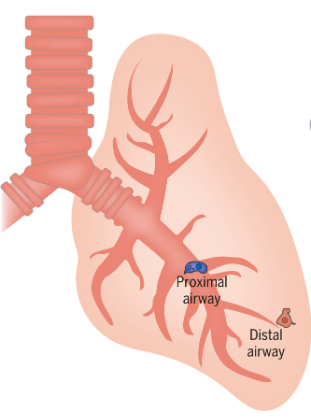

Lung cancer is the leading cause of cancer death in the United States, and nearly a third of these cancers are driven by mutations in the KRAS gene. Long considered an “undruggable” cancer target, mutant KRAS proteins are known to rewire alveolar type II progenitor (AT2) cells, which line the lung surface and are responsible for repairing lung tissue after injury. KRAS inhibitors are now making their way to the clinic, but as yet only a subset of patients respond, highlighting the need to better understand the role of mutant KRAS in the development of lung cancer.

The Damon Runyon Cancer Research Foundation has named 16 new Damon Runyon Fellows, exceptional postdoctoral scientists conducting basic and translational cancer research in the laboratories of leading senior investigators. This prestigious Fellowship encourages the nation's most promising young scientists to pursue careers in cancer research by providing them with independent funding ($300,000 total) to investigate cancer causes, mechanisms, therapies, and prevention.

Some cancer cells, such as those in lung tumors, change drastically in appearance and behavior when they develop resistance to targeted therapies. The result of these changes, collectively known as histological transformation (HT), is a more aggressive tumor type. HT necessitates a new therapeutic strategy, since the original oncogene is no longer driving the tumor’s spread. But first, researchers have to find out which genes have assumed control.

The Damon Runyon Cancer Research Foundation has named six new Damon Runyon Clinical Investigators. The recipients of this prestigious award are outstanding, early-career physician-scientists conducting patient-oriented cancer research at major research centers under the mentorship of the nation's leading scientists and clinicians. The Clinical Investigator Award program was designed to increase the number of physicians capable of translating scientific discoveries into new treatments for cancer patients.

Blood stem cells, like all living things, lose their regenerative capacity with age. Because blood stem cells generate not only blood but all the cells in our immune system, age-related dysfunction can lead to a plethora of systemic issues in older adults, including blood cancer. There is, of course, no stopping time. But according to a new study from researchers at the Columbia Stem Cell Initiative, including Damon Runyon Fellow James Swann, VetMB, DPhil, there may be a way to slow down the clock.

The Damon Runyon Cancer Research Foundation held its Annual Breakfast at The Metropolitan Club in New York on Wednesday, June 12, 2024. The event raised over $1.5 million to support promising early-career scientists pursuing innovative strategies to prevent, diagnose, and treat all forms of cancer.

Prostate cancer is a disease with many subtypes, some of which are more difficult to treat than others. While most prostate cancer cells rely on androgen hormones to grow—allowing androgen blockers to emerge as an effective therapy—15 to 20 percent of prostate cancers evolve to be “androgen-independent.” One such subtype is known as castration-resistant neuroendocrine prostate cancer (CRPC-NE), for which chemotherapy is the primary treatment strategy.

One in eight women in the U.S. will develop breast cancer during their lifetime, and for many, the best treatment option is surgical removal of the tumor, known as a lumpectomy. Unfortunately, the surgical tools currently in use do not always accurately identify the extent of the tumor, necessitating a second surgery for up to a third of patients.